Game Engine - 5 | Terrain Generation and Rendering

It has been quite some time since the last post regarding the development of this engine and admittedly, not much has changed. I took a small break to work on other things but still churned out basic terrain generation and an arguably better method of rendering the voxels which I'll describe further below. Also, I'm changing the name of this series to just 'Game Engine' as I'm getting tired of the length of the original.

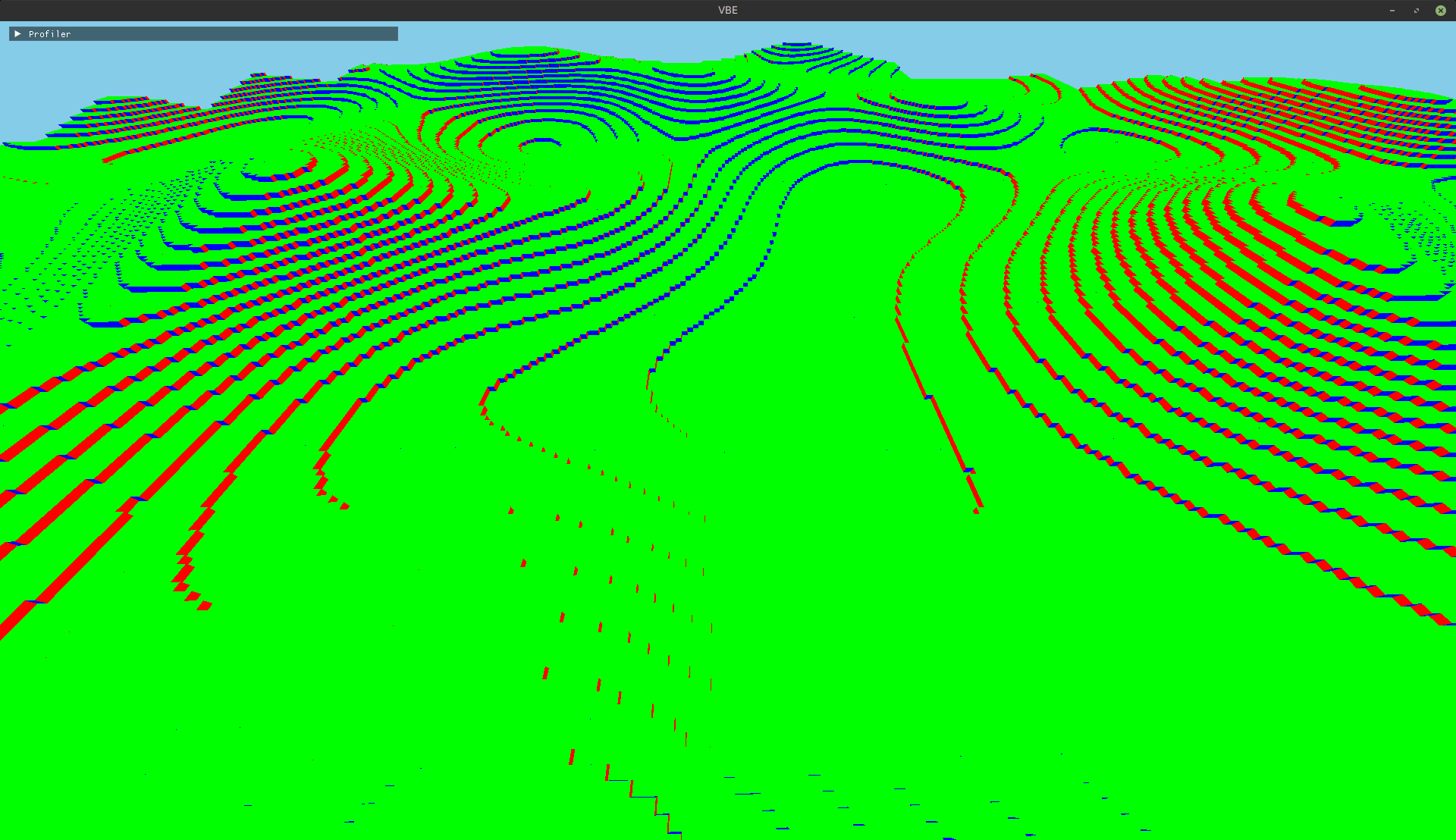

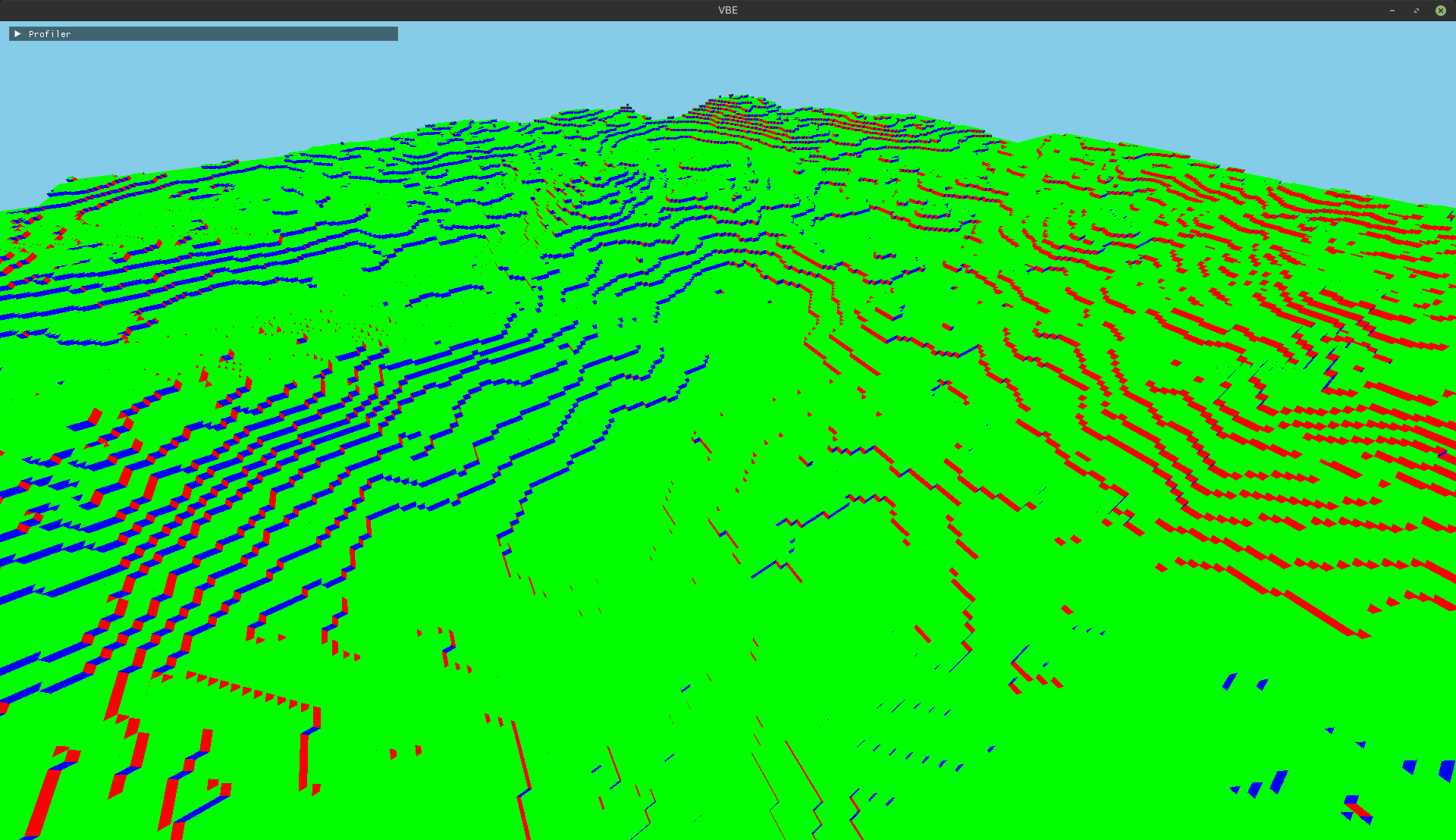

Terrain Generation

I went with a simple perlin noise approach to terrain generation, using a library called FastNoiseLite, a very portable noise library for a multitude of different languages. For C++, it’s just a single-header file so integration is trivial.

The generation of the voxel data for our terrain is simple enough: we initialize the noise, set it to some seed, and poll points in the noise using the absolute XZ position of the voxel to get its Y position, or height, of the voxel.

This terrain, while alright, is very clean, too clean for realistic terrain, so how can we fix this? Octaves.

In short, octaves is just the practice of producing terrain with a multi-sampling approach where each subsequent sample (octave) adds to the previous sample. So for each point in the chunk, we make N number of samples to get our final voxel Y position.

To add more randomness to the sampling, we change the seed at every octave and change how we sample from the noise (in my implementation, I multiple the sampling point by the octave level). There are also some equations that balance out the stacking of samples so the terrain remains stable. If you want more information on this technique I recommend checking out this article called Making Maps With Noise Functions. This is what I referrenced to help develop my terrain generator.

After some experimentation, I found 6 octaves to be the limit before changes become imperceivable. And I’d say the terrain is much more realistic than before.

Additional Notes

First, each chunk is 32x32x32 voxels in size and it will become more apparent as to why in the next major section.

Second, I also implemented several additional functions, mechanisms, and structures to facilitate conditional terrain generation and deletion. This allowed me to define a range around the camera that chunks should be generated/rendered meaning you can now explore the environment infinitely (in theory at least) while maintaining a sustainable number of tracked and rendered chunks.

Third, the terrain is only one block in depth meaning that for each of these 32x32x32 voxel chunks, there are only 32x32 total voxels that make up the terrain in each chunk.

Rendering Optimizations

There were a series of small optimizations I always had in the back of my mind when developing the engine and after implementing the terrain generation, I decided to implement some of them.

Even More Primitive Voxel Representation

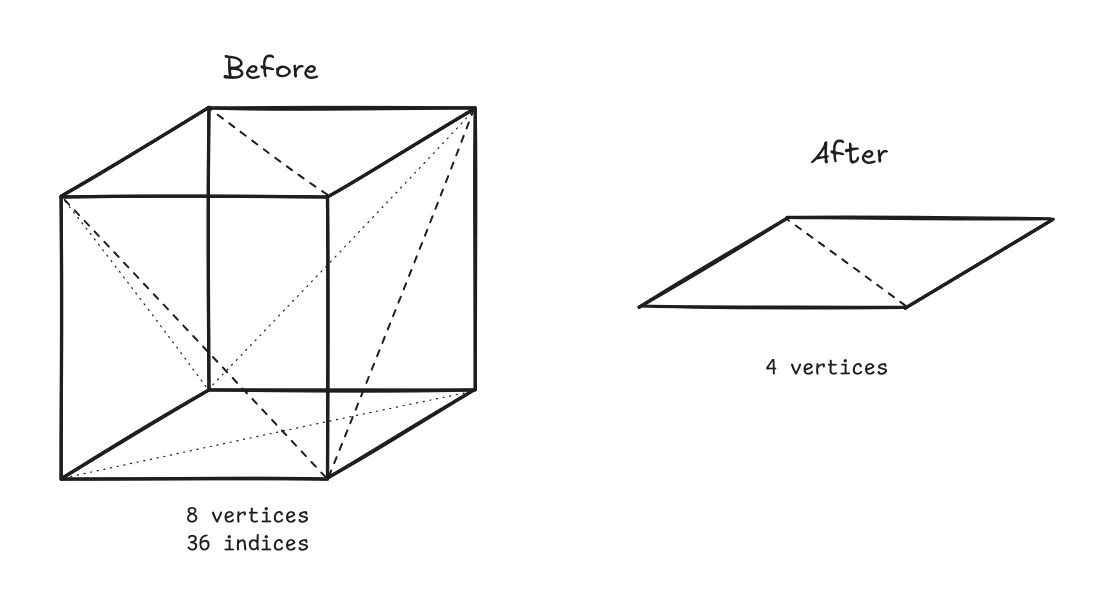

When instancing the voxels in the engine, I was using an entire voxel mesh meaning a whole 6-sided 12-triangle cube was rendered per instance.

There are some problems with this approach however. Mainly, there’s no control over which sides of the cube you want to render (in my case at least). So a case could, and very often did, occur where two voxels which sat side-by-side to each other would have a shared same, and thus hidden, face. But since we don’t have control over which faces of the voxel get rendered, these two faces would still be processed through the vertex shader. To fix this, I made the instancing mesh more primitive.

Instead of the voxel mesh being a whole cube, I simplified it to a single face of the cube, specifically the top or Y-positive face. This provides two immediate benefits alongside some problems we’ll also address.

First, instead of storing 8 vertex positions and an index buffer containing

36 indices defining the cube’s construction, I could minimize the data to just

4 vertex positions and by using the GL_TRIANGLE_STRIP command during rendering,

I eliminiate the need for the index buffer.

Second, now that each face of a voxel is considered its own instance, we can selectively prune hidden faces and only store visible faces in our instancing data.

Now for the problems.

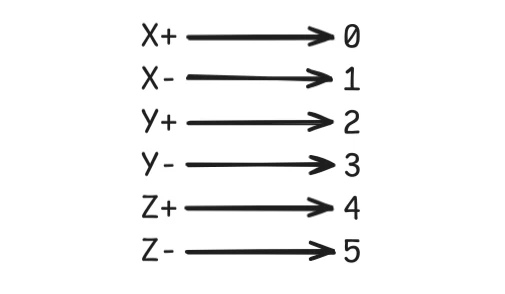

First, if the mesh is a single face (Y-positive face), how do we actually render the specific side of the voxel that some set of instance data represents? Well we can just provide an additional value that represents the side of the voxel the instance represents.

There are 6 total sides to a voxel so by passing this additional value, we can indicate to the vertex shader which side the instance represents and manipulate (rotate and shift) the vertex data in the shader itself.

While this does mean we need to store an additional byte of data per instance, there’s a better way to contain our data that we’ll go over in the next section.

Data Packing

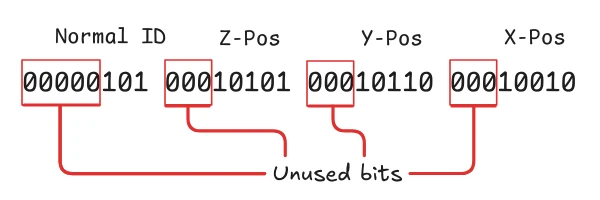

Right now, the positional data for each instance is represented by 3 bytes of data for the X, Y, and Z position. And now we have another 1 byte for our face direction which I’ll call the normal ID from now on.

When we take a closer look at our data, it becomes quite apparent that we’re not utilizing the full width of our types. Since our chunks are only 32 units wide along each axis, we’re only using 5 bits of the total 8 bits available to us. Moreover, there are only 6 possible values for our normal ID which can be feasibly respresented with just 3 bits.

So in theory, we could represent our instance data, besides the color data, with just 18 bits, so let’s try doing this.

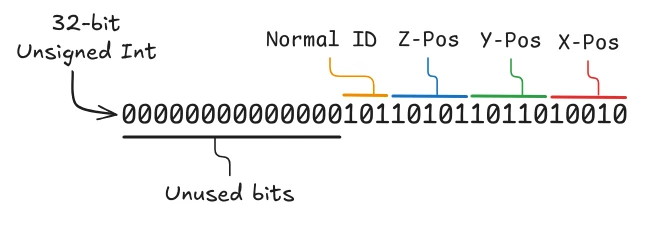

Now in GLSL, which is the shading language for OpenGL, the smallest width data type that can represent our data is a 32-bit unsigned int, so we’ll pack all our data into this single type.

Now you might be thinking, “this is still 4-bytes of data, how is this an optimization?”, which is extremely valid as the benefits of our data packing strategy aren’t immediately obvious.

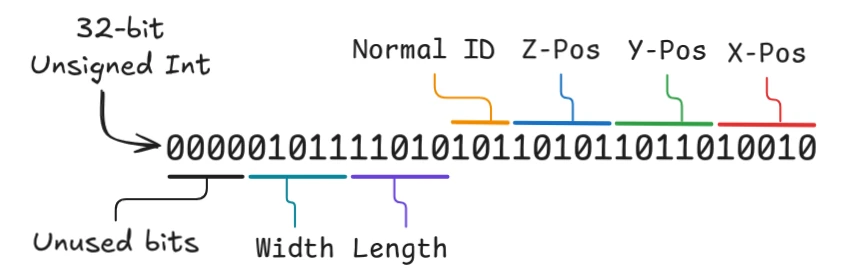

The biggest benefit is what we can do with the extra 14 bits of data left over. The next major development will be on greedy meshing where we try to represent adjacent and equal faces with a single large face. To do this, we need the capacity to define the length and width of our face in the instancing data. Since, again, our chunks are 32 units along each axis, we need at least 10 bits of data, 5 for the length and 5 for the width.

In the previous implementation, we would need an additional 2 bytes of data to store the width and length but now that we’ve packed our data, we can utilize the unused bits to store this information. Plus, we still have 4 bits leftover that we could use for later. And yes, this is a bit of premature optimization but the next development of the engine will be to implement the greedy meshing so it’ll all work out.

Another potential benefit to this data packing is in regards to how GLSL actually handles data types smaller than 32 bits. In GLSL, most, if not all, major data types are 32 bits wide meaning when we pass say a vec3 of unsigned bytes to the shader, each component will get upconverted to a 32-bit type. So in theory, packing our data into a single 32-bit unsigned int is already more efficient. However, I put this as a note because I'm not entirely sure as to how GLSL handles the data internally so this benefit is only speculation on my part. I'll need to read more into how data works within GLSL shaders to get a formal answer to this.

Muli Draw Indirect

While not a direct optimization, the new implementation of our instance data makes multi draw indirect calls more useful to us. In our current implementation, we draw all the instance data which, provided our same face culling, renders all potentially visible faces of a chunk.

However, we can selectively choose what portions of our instance data we want

to render using a muli draw indirect call, specifically

glMultiDrawArraysIndirect.

Now we could have used this in our previous implementation but its usage would have been limiting. Selecting specific portions of the instance data to render, and thus excluding others, would have just left holes in our terrain as it would have eliminated entire voxels.

But now that our instance data represents individual faces, so long as we arrange the instance data in our buffers appropriately, we can essentially exclude specific face groups from ever being rendered. The most prominent being the faces that are facing away from the camera at that moment.

This is another mechanism that I have yet to implement but the tools to do so are already there so I’ll likely implement this soon.

Benefits?

Of course, all of this work would be fairly useless if none of it resulted in any substantial improvement in performance, so did it?

Well not really? On my system, which has an i5-10400, 16GB of RAM, and an RTX 3070, the average FPS went from around 700 to around 750 which is about a 7% improvement in performance.

However, when I ran the same tests on my laptop which has a Ryzen 7 7730U, 40GB of RAM, and integrated Vega 8 graphics, the average FPS went from around 240 to around 400 which is almost a 70% improvement in performance!

Although my sample size is small (2 samples), I think the optimizations I’ve made here have led to partially negligible to significant improvements to performance. So I’ll take that.

Next

As said earlier, probably greedy meshing. Though I’m also gonna take a slight break from this project to go work on other things.